Difference between revisions of "Robotic"

(Created page with "Here you can find a very brief overview of robots used in manufacturing. It talks about what is it that makes a machine a robot, what differentiates the various types of robot...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Category:Technologies]] | ||

| + | |||

Here you can find a very brief overview of robots used in manufacturing. It talks about what is it that makes a machine a robot, what differentiates the various types of robots, and different ways robots can move. | Here you can find a very brief overview of robots used in manufacturing. It talks about what is it that makes a machine a robot, what differentiates the various types of robots, and different ways robots can move. | ||

| Line 390: | Line 392: | ||

https://blogs.mathworks.com/racing-lounge/2018/04/11/robot-manipulation-part-1-kinematics/ | https://blogs.mathworks.com/racing-lounge/2018/04/11/robot-manipulation-part-1-kinematics/ | ||

| + | It should be noted here that the information gathering was drawn by Alexandre Dubor, Kunal Chadha, Ricardo Mayor Luque and many people at IAAC | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | = Related Machines at IAAC = | |

| + | <gallery widths=350 heights=200 style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | File:Machines 13.jpg|Kuka KR 150 L110-2 - 6 Axis Robotic Arm|link=Kuka KR 150 L110-2 | ||

| + | File:ABB140.jpg|ABB IRB 140 - 6 Axes Robot|link= ABB_IRB_140_-_6_Axes_Robot | ||

| + | File:ABB_IRB_120.jpg|ABB IRB 120 - 6 Axes Robot|link= ABB_IRB_120_-_6_Axes_Robot | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | = Related Software at IAAC = | |

| − | + | <gallery widths=350 heights=200 style="text-align:center"> | |

| − | + | File:Robots logo.jpg|link= ROBOTS | |

| − | + | File:Kuka_prc_logo.jpg|link= KUKA PRC | |

| − | + | </gallery> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

Latest revision as of 18:04, 3 November 2020

Here you can find a very brief overview of robots used in manufacturing. It talks about what is it that makes a machine a robot, what differentiates the various types of robots, and different ways robots can move.

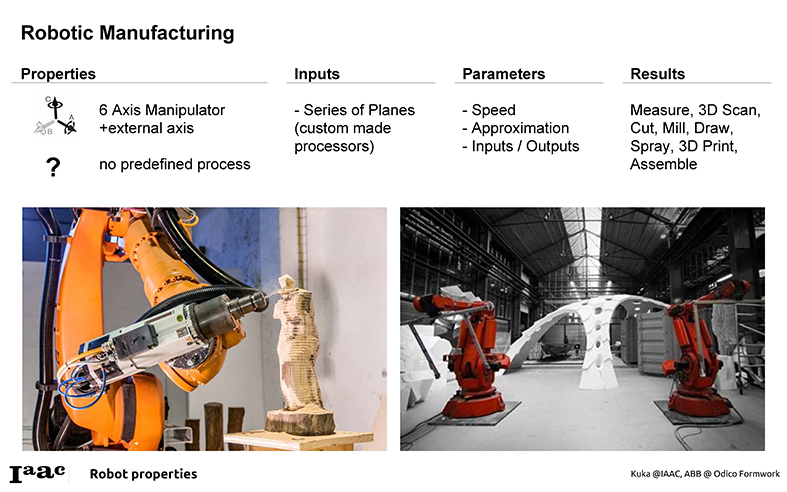

Robot properties

Contents

Terminology

Karl Capek coined the term robot in 1920. He was a Czech playwright who wrote R.U.R. which stands for Rosumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots).

The term robot might comes from the Czech words robota and robotník, which literally means "work" and "worker" respectively. However, the word robota also means "work" or "serf labour" in Slovak.

Modern definition of a robot

Encyclopedia Britannica's definition of a robot is as follows:

"Any automatically operated machine that replaces human effort, though it might not resemble human beings in appearance or perform functions in a humanlike manner."

The Robotics Primer (which we also highly recommend), Maja J. Mataric uses the following definition:

"A robot is an autonomous system which exists in the physical world, can sense its environment, and can act on it to achieve some goals."

Another definition by Lentin Joseph in Learning Robotics Using Python, 2015 :

"A robot is an autonomous system which exists in the physical world, can sense its environment, and can act on it to achieve some goals."

History

(Chapter extracted from the book "Learning Robotics Using Python, Lentin Joseph, 2015.")

It's quite difficult to pinpoint a precise date in history, which we can mark as the date of birth of the first robot. For one, we have established quite a restrictive definition of a robot previously; thus, we will have to wait until the 20th century to actually see a robot in the proper sense of the word.

Until then, let's note at least the honourable mentions:

The first one that comes close to a robot is a mechanical bird called "The Pigeon". This was postulated by a Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum in the 4th century BC and was supposed to be propelled by steam. It cannot be considered a robot by our definition (not being able to sense its environment already disqualifies it), but it comes pretty comes for its age. Over the following centuries, there were many attempts to create automatic machines, such as clocks measuring time using the flow of water, life-sized mechanical figures, or even first programmable humanoid robots (it was actually a boat with four automatic musicians on it).

Also, we must turn our attention to the Leonardo Da Vinci's notebooks that were rediscovered in the 1950s. They contain a complete drawing of a 1945 humanoid (a fancy word for a mechanical device that resembles humans), which looks like an armoured knight. It seems that it was designed so that it could sit up, wave its arms, move its head, and most importantly, amuse royalty.

Another example that should not be overlooked is the work developed by Jacques de Vaucanson. In the 18th century, Jacques de Vaucanson created three automata: a flute player that could play twelve songs, a tambourine player, and the most famous one, "The Digesting Duck".

The problem with all these is that they are very disputable as there is very little (or none) historically trustworthy information available about these machines.

Our list will not be complete if we omitted these robot-like devices that came about in the following century. Many of them were radio-controlled, such as Nikola Tesla's boat, which he showcased at Madison Square Garden in New York. You could command it to go forward, stop, turn left or right, turn its lights on or off, and even submerge. All of this did not seem too impressive at that time because the press reports attributed it to "mind control".

At this point, we have once again reached the time when the term robot was used for the first time. As we said before, it was in 1920 when Karel Čapek used it in his play, R.U.R. Two decades later, another very important term was coined. Issac Asimov used the term robotics for the first time in his story "Runaround" in 1942. Asimov wrote many other stories about robots and is considered to be a prominent sci-fi author of his time.

However, in the world of robotics, he is known for his three laws of robotics:

• First law: A robot may not injure a human being or through inaction allow a human being to come to harm.

• Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the first law.

• Third law: A robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the first or second law.

After a while, he added a zeroth law:

• Zeroth law: A robot may not harm humanity or by inaction allow humanity to come to harm.

These laws somehow reflect the feelings people had about machines they called robots at that time. Seeing enslavement by some sort of intelligent machine as a real possibility, these laws were supposed to be some sort of guiding principles one should at least keep in mind, if not directly follow when designing a new intelligent machine. Also, while many were afraid of the robot apocalypse, the time has shown that it's still yet to come. In order for it to take place, machines will need to get some sort of intelligence, some ability to think and act based on their thoughts. Also, while we can see that over the course of history, the mechanical side of robots went through some development, the intelligence simply was not there yet.

This was part of the reason why in the summer of 1956, a group of very wise

gentlemen (which included Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, Herbert Simon, and

Allan Newell) was later called to be the founding fathers of the newly founded field

of Artificial Intelligence. It was at this very event where they got together to discuss

creating intelligence in machines (thus, the term artificial intelligence).

Although their goals were very ambitious, it took quite a while until some interesting results could be presented: One such example is Shakey: a robot built by the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in 1966. It was the first robot (in our modern sense of the word) capable to reason its own actions. The robots built before this usually had all the actions they could execute preprogrammed. On the other hand, Shakey was able to analyze a more complex command and split it into smaller problems on his own.

The following image of Shakey is taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ File:ShakeyLivesHere.jpg:

Shakey, resting in the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California

His hardware was quite advanced too. He had collision detectors, sonar range finders, and a television camera. He operated in a small closed environment of rooms, which were usually filled with obstacles of many kinds. In order to navigate around these obstacles, it was necessary to find a way around these obstacles while not bumping into something. Shakey did it in a very straightforward way.

This is considered to be one of the most fundamental building blocks not only in the field of robotics or artificial intelligence but also in the field of computer science as a whole.

Applications

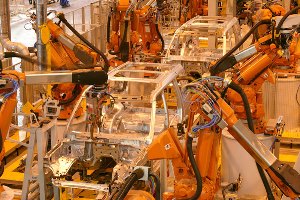

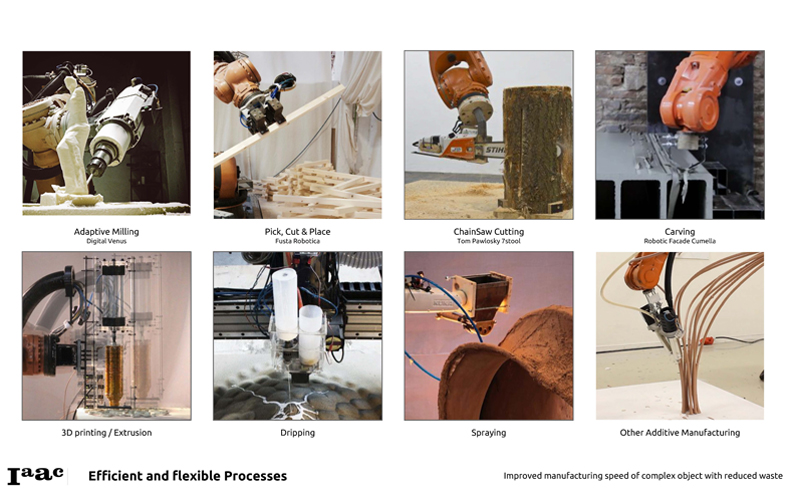

The application is the type of work that the robot is designed to do. Robot models are created with specific applications or processes in mind. Different applications will have different requirements. For instance, a painting robot will require a small payload but a large movement range and be explosion proof. On the other hand, an assembly robot will have a small workspace but will be very precise and fast. Depending on the target application, the industrial robot will have a specific type of movement, linkage dimension, control law, software and accessory packages. Below are some types of applications:

Welding robots

Material handling robots

palletizing robot

Painting robot

Assembly robot

Experimental processes @ IAAC

General principles

Kinematics

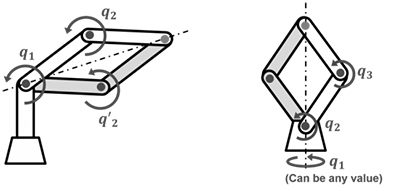

The type of movement is dictated by the arrangement of joints (placement and type) and linkages (Serial or Parallel).

Secondly, taking the article:(Robot Manipulation: Kinematics by Sebastian Castro. 2018) as a definition reference of Kinematics:

It's worth to highlight a quick comparison of kinematics and dynamics:

Kinematics is the analysis of motion without considering forces. Here, we only need geometric properties such as lengths and degrees of freedom of the manipulator bodies.

Dynamics is the analysis of motion caused by forces. In addition to geometry, we now require parameters like mass and inertia to calculate the acceleration of bodies. Robot manipulators are often composed of several joints. Joints are composed of revolute (rotating) or prismatic (linear) degrees of freedom (DOF). Therefore, joint positions can be controlled to place the end effector of the robot in 3D space.

If you know the geometry of the robot and all its joint positions, you can do the math and figure out the position and orientation of any point on the robot. This is known as forwarding kinematics (FK).

The more frequent robot manipulation problem, however, is the opposite. We want to calculate the joint angles needed such that the end effector reaches a specific position and orientation. This is known as inverse kinematics (IK).

Robot types

Serial

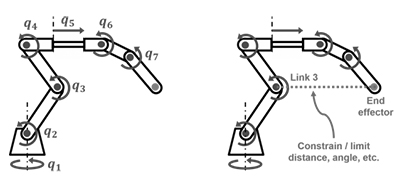

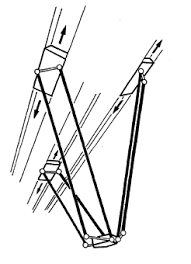

Serial robots are the most common. They are composed of a series of joints and linkages that go from the base to the robot tool.

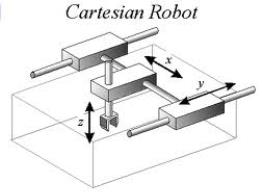

Cartesian robots

Cartesian robots are robots that can do 3 translations using linear slides.

Articulated

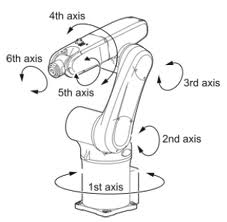

In particular 6-axis robots are robots that can fully position their tool in a given position (3 translations) and orientation (3 orientations)

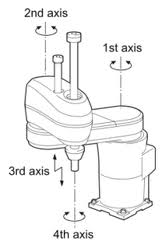

SCARA robots

Scara robots are robots that can do 3 translations plus a rotation around a vertical axis.

Redundant robots

Redundant robots can also fully position their tool in a given position. But while 6-axis robots can only have one posture for one given tool position, redundant robots can accommodate a given tool position under different postures. This is just like the human arm that can hold a fixed handle while moving the shoulder and elbow joints.

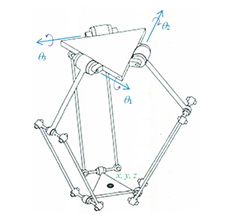

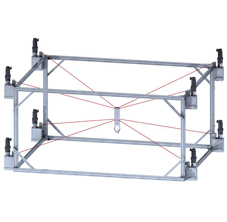

Parallel

Parallel robots come in many forms. Parallel industrial robots are made in such a way that you can close loops from the base, to the tool and back to the base again. It's like many arms working together with the robot tool. Parallel industrial robots typically have a smaller workspace (try to move your arms around while holding your hands together vs the space you can reach with a free arm) but higher accelerations, as the actuators don't need to be moved: they all sit at the base.

Delta or Spider Robot

Cable Robot

Others

External Axis

Linear or Rotary

Dual-arm robots

Dual-arm robots are composed of two arms that can work together on a given workpiece.

Collaborative industrial robots

There is a new qualifier that has just recently been used to classify an industrial robot, that is to say, if it can collaborate with its human co-workers. Collaborative robots are made in such a way that they respect some safety standards so that they cannot hurt a human. While traditional industrial robots generally need to be fenced off away from human co-workers for safety reasons. Collaborative robots can be used in the same environment as humans. They can also usually be taught instead of programmed by an operator.

Basic terminologies

Work Cell: All the equipment needed to perform the robotic process (robot, table, fixtures, etc.)

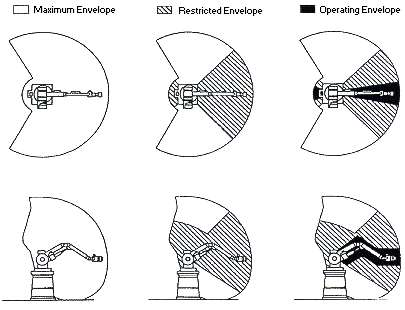

Work Envelope: All the space the robot can reach.

Degrees of Freedom: The number of movable motions in the robot. To be considered a robot there needs to be a minimum of 4 degrees of freedom.

Payload: The amount of weight a robot can handle at full arm extension and moving at full speed.

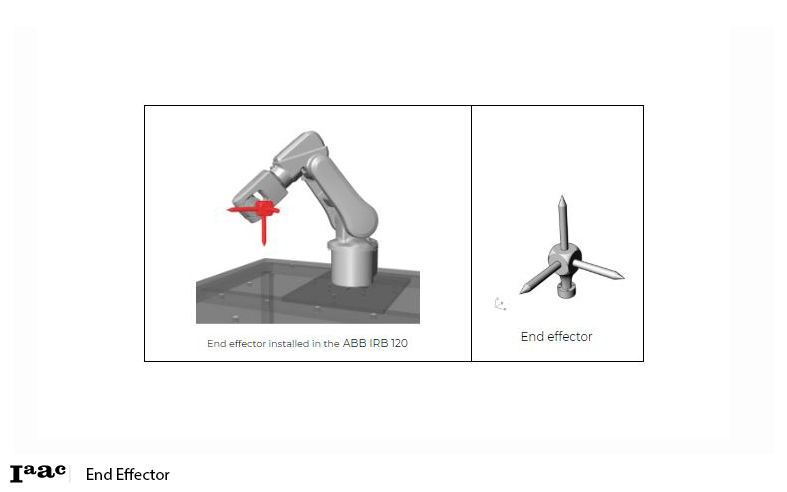

End Effector: The tool that does the work of the robot. Examples: Welding gun, paint gun, gripper, etc.

Manipulator: The robot arm (everything except the End of Arm Tooling).

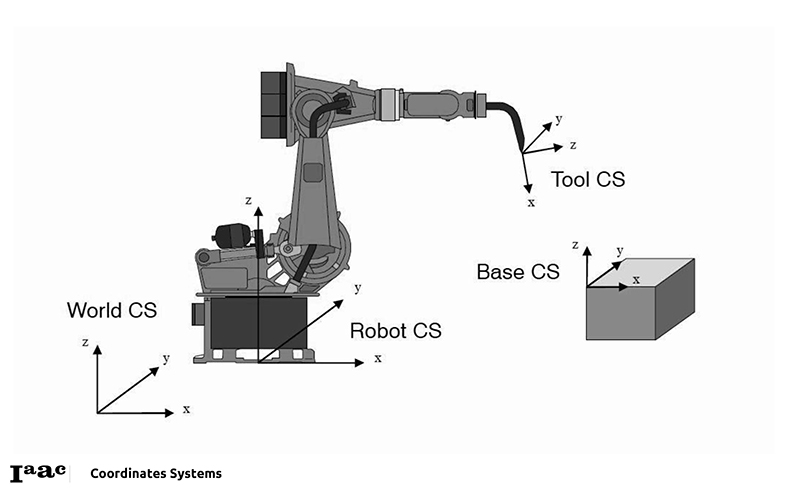

TCP: Tool Center Point. This is the point (coordinate) that we program in relation to.

Positioning Axes: The first three axes of the robot (1, 2, 3). Base / Shoulder / Elbow = Positioning Axes. These are the axes near the base of the robot.

Orientation Axes: The other joints (4, 5, 6). These joints are always rotary. Pitch / Roll / Yaw = Orientation Axes. These are the axes closer to the tool.

Coordinates Systems

Types of Motion

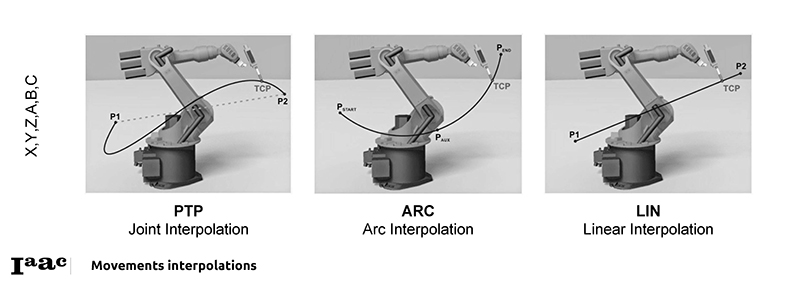

Robot Programming allows us to develop several motion types:

- PTP: Point To Point

The robot guides the TCP along the fastest path to the endpoint. The fastest path is generally not the shortest path and is thus not a straight line. As the motions of the robot axes are rotational, curved paths can be executed faster than straight paths. The exact path of the motion cannot be predicted.

- ARC: Arc interpolation

The robot guides the TCP at a defined velocity along a circular path to the endpoint. The circular path is defined by a start point, auxiliary point and endpoint.

- LIN: Linear

The robot guides the TCP at a defined velocity along a straight path to the end point. This path is predictable.

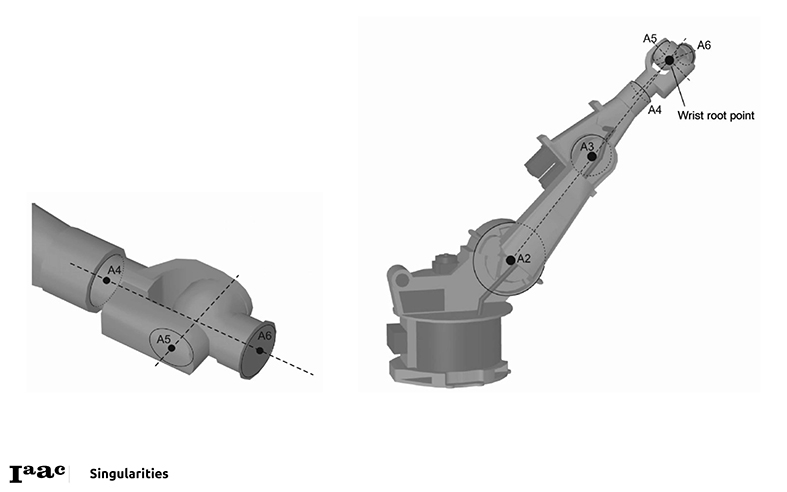

Singularities

(information extracted from Kinematic Singularities - Peter Donelan. Victoria University of Wellington. New Zealand, 2010)

This is a condition in which the manipulator loses one or more degrees of freedom and change in joint variables does not result in change in end effector location and orientation variables. This is a case when the determinant of the Jacobian matrix is zero ie. It is a rank deficit.

Intuitively, Singularities play a significant role in the design and control of robot manipulators. Singularities of the kinematic mapping, which determines the position of the end–effector in terms of the manipulator’s joint variables, may impede control algorithms, lead to large joint velocities, forces and torques and reduce instantaneous mobility.

However they can also enable fine control, and the singularities exhibited by trajectories of the points in the end–effector can be used to mechanical advantage. A number of attempts have been made to understand kinematic singularities and, more specifically, singularities of robot manipulators, using aspects of the singularity theory of smooth maps.

Hazards

(Chapter extracted from Industrial Robots and Robot Industry Safety, chapter 4. United States, Department of Labor. https://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/otm_iv/otm_iv_4.html)

The operational characteristics of robots can be significantly different from other machines and equipment. Robots are capable of high-energy (fast or powerful) movements through a large volume of space even beyond the base dimensions of the robot. The pattern and initiation of movement of the robot is predictable if the item being "worked" and the environment are held constant. Any change to the object being worked (i.e., physical model change) or the environment can affect the programmed movements.

Robot's work envelope

Some maintenance and programming personnel may be required to be within the restricted envelope while power is available to actuators. The restricted envelope of the robot can overlap a portion of the restricted envelope of other robots or work zones of other industrial machines and related equipment. Thus, a worker can be hit by one robot while working on another, trapped between them or peripheral equipment, or hit by flying objects released by the gripper.

A robot with two or more resident programs can find the current operating program erroneously calling another existing program with different operating parameters such as velocity, acceleration, or deceleration, or position within the robot's restricted envelope. The occurrence of this might not be predictable by maintenance or programming personnel working with the robot. A component malfunction could also cause an unpredictable movement and/or robot arm velocity.

Additional hazards can also result from the malfunction of, or errors in, interfacing or programming of other process or peripheral equipment. The operating changes with the process being performed or the breakdown of conveyors, clamping mechanisms, or process sensors could cause the robot to react in a different manner.

Types of Accidents. Robotic incidents can be grouped into four categories: a robotic arm or controlled tool causes the accident, places an individual in a risk circumstance, an accessory of the robot's mechanical parts fails, or the power supplies to the robot are uncontrolled.

Impact or Collision Accidents. Unpredicted movements, component malfunctions, or unpredicted program changes related to the robot's arm or peripheral equipment can result in contact accidents.

Crushing and Trapping Accidents. A worker's limb or another body part can be trapped between a robot's arm and other peripheral equipment, or the individual may be physically driven into and crushed by other peripheral equipment.

Mechanical Part Accidents. The breakdown of the robot's drive components, tooling or end-effector, peripheral equipment, or its power source is a mechanical accident. The release of parts, failure of gripper mechanism, or the failure of end-effector power tools (e.g., grinding wheels, buffing wheels, deburring tools, power screwdrivers, and nut runners) are a few types of mechanical failures.

Other Accidents. Other accidents can result from working with robots. Equipment that supplies robot power and control represents potential electrical and pressurized fluid hazards. Ruptured hydraulic lines could create dangerous high-pressure cutting streams or whipping hose hazards. Environmental accidents from arc flash, metal spatter, dust, electromagnetic, or radio-frequency interference can also occur. In addition, equipment and power cables on the floor present tripping hazards.

Sources of Hazards. The expected hazards of machine to humans can be expected with several additional variations, as follows.

Human Errors. Inherent prior programming, interfacing activated peripheral equipment, or connecting live input-output sensors to the microprocessor or a peripheral can cause dangerous, unpredicted movement or action by the robot from human error. The incorrect activation of the "teach pendant" or control panel is a frequent human error. The greatest problem, however, is over familiarity with the robot's redundant motions so that an individual places himself in a hazardous position while programming the robot or performing maintenance on it.

Control Errors. Intrinsic faults within the control system of the robot, errors in software, electromagnetic interference, and radio frequency interference are control errors. In addition, these errors can occur due to faults in the hydraulic, pneumatic, or electrical subcontrols associated with the robot or robot system.

Unauthorized Access. Entry into a robot's safeguarded area is hazardous because the person involved may not be familiar with the safeguards in place or their activation status.

Mechanical Failures. Operating programs may not account for cumulative mechanical part failure, and faulty or unexpected operation may occur. Environmental Sources. Electromagnetic or radio-frequency interference (transient signals) should be considered to exert an undesirable influence on robotic operation and increase the potential for injury to any person working in the area. Solutions to environmental hazards should be documented prior to equipment start-up.

Power Systems. Pneumatic, hydraulic, or electrical power sources that have malfunctioning control or transmission elements in the robot power system can disrupt electrical signals to the control and/or power-supply lines. Fire risks are increased by electrical overloads or by use of flammable hydraulic oil. Electrical shock and release of stored energy from accumulating devices also can be hazardous to personnel. Improper Installation. The design, requirements, and layout of equipment, utilities, and facilities of a robot or robot system, if inadequately done, can lead to inherent hazards.

Robotic programming

Take a look into Software>Robotic programming: [[1]]

Credits & References

All the above information comes from the following different sources:

Learning Robotics Using Python, Lentin Joseph. Packt Publishing Ltd, May 27, 2015.

Kinematic Singularities - Peter Donelan. Victoria University of Wellington. New Zealand, 2010

KUKA Programming manual, 2010

https://github.com/visose/Robots/

https://blogs.mathworks.com/racing-lounge/2018/04/11/robot-manipulation-part-1-kinematics/

It should be noted here that the information gathering was drawn by Alexandre Dubor, Kunal Chadha, Ricardo Mayor Luque and many people at IAAC